Strategic Threat and Risk Assessment of Violence Against Women and Girls

Strategic Threat and Risk Assessment of Violence Against Women and Girls

May 2023

Read the PDF version of the report

Foreword

In February 2023 the Home Secretary included violence against women and girls (VAWG) within the strategic policing requirement (SPR) which recognises VAWG as a national threat alongside terrorism and serious and organised crime.

In February 2023 the Home Secretary included violence against women and girls (VAWG) within the strategic policing requirement (SPR) which recognises VAWG as a national threat alongside terrorism and serious and organised crime.

This first national strategic threat risk assessment (STRA) of VAWG aims to provide a better understanding of the influences and levers that contribute to VAWG being a national threat. Developing this understanding is a significant step in helping policing to improve its response as resources are finite and can be more effectively targeted. This understanding will also help inform police and crime commissioners and chief constables when considering the SPR.

The VAWG delivery framework, developed in 2021, aimed to coordinate and standardise the policing of VAWG and focused on the areas that policing could improve immediately. The framework prioritised three pillars of activity : improving trust and confidence in policing, relentlessly pursuing perpetrators and creating safer spaces.

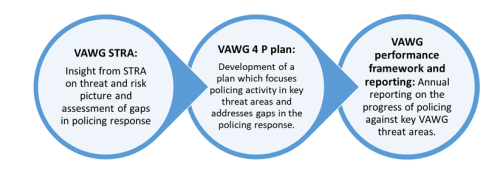

Whilst our focus remains on the three pillars, the insight gained from this STRA will inform the development of a four ‘P’ approach within each: Preventing VAWG, Pursuing VAWG perpetrators, Preparing policing and working with other agencies to better combat VAWG, and Protecting those at risk of VAWG. The plan will provide policing with activities to tackle VAWG threat areas and their impact will be assessed through annual performance reporting.

This STRA will be reviewed annually and with improved data, insight from partners and information from the third sector, it will mature over time.

DCC Maggie Blyth, National Police Chiefs’ Council Violence Against Women and Girls Coordinator

Introduction

The STRA provides an assessment of the influences and levers that contribute to VAWG being a national threat, it prioritises threats and provides an analysis of policing’s future capability and capacity to respond. The insight will equip policing leads and forces to inform strategic planning and decision making. It also highlights gaps in existing knowledge to allow policing and partners to focus activity to improve our shared understanding.

Scope

This assessment covers the breadth of VAWG including:

- Domestic abuse

- Rape and serious sexual offences

- Child sexual abuse and exploitation – for female victims aged 10 years and over (in line with the NPCC VAWG definition which incorporates victims aged 10+)

- Modern slavery and human trafficking

- Honour based abuse

- Stalking and harassment

- Adult sexual exploitation and sex work

- Tech enabled VAWG which includes online harassment

- VAWG in different space types: public, private and in places of education

- Spiking

- Involuntary celibates (incels)

The crimes in this list broadly align to the national policing definition specified in the NPCC VAWG performance and outcomes framework in April 2022. In addition, analysis of information relating to spiking and incels has also been included to add to the threat picture.

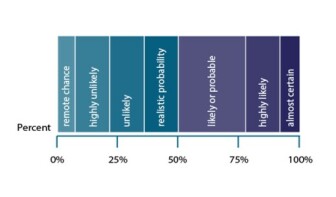

To develop this STRA assessment using the Management of Risk in Law Enforcement (MoRiLE) has been used. Throughout this document, key judgements are provided, some of which provide an assessment of the likelihood of future threats occurring. The Professional Heads of Intelligence Analysis probability yardstick is used to provide a measure of likelihood.

Data feeds

Data feeds

As detailed within the Tackling VAWG: policing performance and insights publication, insight using policing information is challenging. The findings in this STRA are based on the following data feeds:

- Recorded crime and outcomes data from the Home Office provided for the NPCC VAWG performance report

- VAWG problem profiles from local forces

- Office of National Statistics (ONS) data including Crime Survey for England and Wales (CSEW) data

- Force management statements

- Force VAWG action plans

Where there are gaps in policing data, insight has been sought from partner agencies such as the National Crime Agency, the VAWG sector and academia.

Data limitations

National policing data only provides partial insight into the VAWG threat picture To improve the insight, all police forces have shared their problem profiles developed as a result of the national framework. Publicly available data from other organisations was also collated and used to inform this assessment.

Understanding VAWG across minoritised communities is challenging as police data relating to protected characteristics is incomplete. This also has an impact on our understanding of the protected characteristics of perpetrators, the understanding of victim-offender relationships and where offending takes place.

The identification of some offending relies on a manual flagging process on recording systems, which has inherent data accuracy issues. This includes domestic abuse, child sexual exploitation, honour-based abuse and offences taking place online.

Improving the quality of data collection is a priority for policing.

Key findings

The overall picture

The scale and nature of the threat varies across VAWG as does the level of available insight. When considering the threat areas, it is also important to recognise the poly-criminal nature of offenders which can lead to victims being subjected to multiple offences, for example, experiencing sexual assault and coercive control within a domestic setting.

The high-level findings are:

- VAWG accounts for at least 15.8% of all recorded crime and is a significant contributor to demand on policing (Based on a six-month period 1 October 21 – 31 March 22).

- The recently published VAWG statistical bulletin identified that at least 507,827 offences against women and girls were recorded in a six-month period (1 October 2021 – 31 March 2022) in England and Wales. This equates to just under 117 crimes recorded by police, per hour or two crimes per minute.

- There is considerable underreporting of VAWG crimes. The Crime Survey for England and Wales consistently outlines high volumes of women and girls who experience VAWG, such as sexual assault and stalking and harassment, but do not report to police. Barriers to reporting are particularly pertinent in relation to minoritised communities.

Cross cutting themes:

Specific VAWG crime types:

Specific VAWG crime types:

- Data available indicates the following VAWG threat areas have seen increases over recent years: domestic abuse, sexual offences (sexual offences have seen a particularly sharp increase since 2013), stalking and harassment and modern slavery and human trafficking.

- Domestic abuse is a key contributor to VAWG overall. There were 447,431 DA flagged offences for all genders recorded in a six-month period across England and Wales.

- Stalking and harassment accounts for 43% (217,945) of all VAWG and is recorded by forces as varying between 26% and 56% of total VAWG locally. Domestic abuse is a key driver for stalking and harassment, and crime data identifies that 32.4% of all stalking and harassment offences are domestic abuse related.

- Murder or manslaughter aside, exploitation of prostitution and modern slavery and human trafficking were the lowest proportion of recorded VAWG offences. However, there are likely to be significant intelligence gaps around how women and girls are exploited which will impact on the volume of these recorded crime types.

Victims:

- The VAWG victim profile varies across the different crime types.

- A younger victim profile is noted in cases of tech enabled VAWG and sexual offences with 16-25 being the most common age cohort.

- There is clear evidence that intersectionality and women and girls belonging to a minoritised group (including LGBTQ communities or minoritised ethnic groups) are proportionately more greatly impacted by VAWG. This is not limited to prevalence but extends to their experience of and engagement with the criminal justice system.

- Women from black and minoritised groups, in particular migrant women, are particularly reluctant to engage with policing for a variety of reasons including, reduced trust and confidence in policing, immigration concerns and fear of disbelief.

- Women and girls from minoritised communities or migrant women who have no recourse to public funds and encounter further barriers to fleeing abuse are likely to be disproportionately affected.

- Support services are integral in helping victims seek assistance where they feel unable to report to police. Cuts in these services, particularly during a cost of living crisis, will disproportionately affect victims from minoritised communities and migrant women.

- On average, 25% of victims were identified as being repeat victims of VAWG. Some forces were outliers in the proportions of repeat victims identified, with one force reporting a 49% repeat victimisation rate. Where this data was available, there was some evidence that a proportion of repeat victims had other vulnerabilities such as mental health issues and self-harm. This may present barriers to victims in terms of reporting offences to police and emphasises the importance of the role of other agencies to support them during or after the investigative process.

Offenders:

Offenders:

- A small proportion of offenders are commonly responsible for a disproportionate amount of overall VAWG harm committed.

- Across all VAWG threats most perpetrators are male. Where data was available, age profile varied across threat area however data limitations inhibited the ability to provide an accurate offender profile.

- A proportion of VAWG offenders are involved in non-VAWG criminality. This is echoed in the Operation Soteria Buestone year one report which identified that between 41.4% and 58.8% of offenders were linked to more than one offence of any type. This provides policing with additional opportunities to relentlessly pursue VAWG perpetrators.

Places:

- The most common location type for offending was in a private space, mostly in private dwellings, particularly the home.

- Where public space VAWG offending occurred, the most common locations were recorded as high density night-time economy venues or areas with high levels of deprivation.

- Some forces identified that public space VAWG hotspots were most common in town centres or areas with high footfall. This presents policing with opportunities to work with partners such as local authorities and licensed venues to disrupt and prevent offending.

- VAWG in places of education accounted for 2% (on average) of VAWG offences, venues were mostly secondary schools and violence against the person (such as assault) was the most reported.

Response

Digital forensics:

- The increased use of technology has amplified opportunities for digital evidence and investigative opportunities.

- This has placed challenges on policing in both capability and capacity. HMICFRS found that policing is unable to keep pace with the volume of digital evidence from devices which has led to considerable backlog.

- The proliferation of end-to-end encryption and use of the dark web will adversely impact the detection of offenders.

- There is a gap in policing between the specialist knowledge of emerging technology held by specialist investigators and partner organisations and those investigating VAWG.

Criminal justice outcomes and processes:

- It is likely that not all victims contact the police with a view to pursuing a criminal justice outcome, so a criminal charge should not be viewed as the only positive outcome for victims. Further exploration is needed to understand desired outcomes for victims when they do report.

- Data on recorded crimes from 40 forces showed that many VAWG investigations are complex and may not conclude within a six-month period. The most prevalent recorded reason for cases being closed was evidential difficulties and victims not supporting, or withdrawing their support for onward action (38%). This was higher for stalking and harassment cases. Further work is required to understand the reasons behind the high rate of victim attrition across broader VAWG, expanding on the work done by Operation Soteria Bluestone. This could inform a greater understanding of a victim’s view of procedural justice.

- VAWG offences which resulted in a charge accounted for 6% of all crimes which were closed. This was five times higher in cases of exploitation of prostitution and over ten times higher in cases of murder or manslaughter. Further insight is provided in the VAWG performance report.

- Almost half of child sexual abuse and exploitation cases do not progress through the criminal justice system due to victims not supporting a prosecution. A considerable proportion of child sexual abuse and exploitation in the context of VAWG is child-on-child, driven by consensual sharing of self-generated indecent images. Criminalising the children involved through charge or caution, may not always be the right result for the children involved.. There are partnership processes in place which seek to identify other resolution options or support.

Demand:

- Demand exceeding capacity is consistently raised as a concern across policing. In some VAWG cases, where increased complexity is present, this concern can be exacerbated. For example, where victims or perpetrators have mental health needs, the investigation requires the involvement of other agencies, or the offences take place in other jurisdictions.

- Surges in reporting are seen in the aftermath of high profile VAWG incidents, which allows more safeguarding of victims and opportunities to bring offenders to justice.

- Trends in recorded crimes over the past 12 months and forecasts for the next 12 months indicate it is likely that reporting by the public in all VAWG threats (except for spiking and incels) will continue to increase with the continuing focus on VAWG, the threat of tech enabled VAWG is almost certain to increase.

Training and resourcing:

Training and resourcing:

- The 20,000-officer uplift is bringing much needed additional capacity. VAWG-focused training and learning and development opportunities, designed to address VAWG objectives, will continue to support policing’s delivery of an increasing demand landscape. There has been a heavy investment in student officers and extra learning for tutor constables, plus an increase in officers working in public protection.

- Within policing careers in public protection are often perceived as being undervalued, and carrying greater risk and demand than other policing areas. This can lead to higher turnover of staff and burnout for those who do work in this area. The year one Operation Soteria Bluestone report concluded that officers working on rape and serious sexual offences have burnout rates that were worse than frontline medical staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. This contrasts with other risk areas such as firearms or public order which are accredited disciplines with mandatory training and development requirements to support them in managing risk. Public protection is also often seen as the remit solely of public protection teams when in fact it requires a whole force response.

- Many forces reported that there was a substantial shortfall in training courses relating to rape and serious sexual offences relative to demand for places for investigator roles.

Relentless pursuit of perpetrators:

- There is variation in methods for identifying high harm and repeat VAWG perpetrators across policing, and limited evaluated practice although work is progressing in this area. This includes working to improve consistency in the management of protective orders and the recent Government announcement about the development of a digital tool to identify dangerous perpetrators. Furthermore, the Home Office has recently issued guidance on commissioning interventions for domestic abuse perpetrators.

- The VAWG performance report identified issues with the systems for notifying police of civil protective orders. There is currently no national system that ensures policing is sighted on the existence of orders when responding to an incident or when assessing risk. Whilst some orders are applied for by forces, only the force making the application will be advised of this authorisation and for civil orders, such as non-molestation orders, policing is not notified when an order is granted unless a victim chooses to notify them. These issues all impact the ability to enforce orders or use them as a source of information in risk assessment.

Use of data and analysis:

- Developing the policing response to VAWG must be based on a sound understanding of the threat picture. To do this effectively there is a need for investment in local and national analytical and data capabilities. Data is an underused and underinvested asset for policing. Policing struggles to accurately understand demand and impacts from different communities because of data limitations.

- Access to, and analysis of, non-policing data (such as that collected by health, local authorities and other partners) on VAWG will facilitate an improved collective understanding and response to VAWG.

- Investment in analytics and a single data and intelligence repository is crucial and will benefit victims and communities. This includes addressing the decreasing levels of specialist intelligence analytical capability and placing greater emphasis on VAWG and analysis through local policing tasking processes.

External impacts

Trust and confidence in policing:

- Public trust and confidence have been eroded over recent years. A series of high-profile cases have impacted women and minoritised groups’ confidence in policing, particularly in relation to how policing responds to crimes disproportionately affecting women and girls.

- A 2022 IPSOS MORI survey found that White people deemed police to be more trustworthy compared to the level of trust in policing held by ethnic minorities. Women were also found to have less confidence than men that policing is taking VAWG seriously.

- Building trust and confidence remains a key pillar for tackling VAWG and there is evidence of strengthening work across forces supported by the SPR and sharing of best practice nationally.

Cost of living crisis:

Cost of living crisis:

- The current economic crisis was raised by several forces as an emerging threat for VAWG particularly for victims who are financially dependent, economically vulnerable or people who are at risk of increased exploitation through forms of MSHT.

- Many women find they are unable to cover living costs and support their children on a single or limited income which will likely make it harder for women to escape abuse.

- The third sector is also being impacted by increased costs and inflation and are having to redirect funds to cover running costs such as energy.

- Government funding challenges will likely impact the funding available to Police and Crime Commissioners to commission support services which could impact on the availability of support offered to vulnerable victims.

- Women and girls from minoritised communities or migrant women who have no recourse to public funds and encounter further barriers to fleeing abuse are likely to be disproportionately affected.

Partnership working:

- Policing recognises that it cannot tackle VAWG alone; the issues require a coordinated response across partnerships, as recognised by the Government’s VAWG strategy and Policing Vision 2030 but there is variation across England and Wales in how policing works with partners in its response to VAWG.

- There is also variation in how partners within community safety partnerships and police and crime commissioners prioritise VAWG.

- All VAWG partners have a significant role to play in prevention, response and developing support to victims such as independent sexual violence advisors (ISVAs) and independent domestic violence advisors (IDVAs).

- Effective data sharing between policing and partners is vital to allow identification of VAWG offending and offenders as disclosures are often made to partners before policing.

- The new serious violence duty (SVD) sets out requirements on policing and partners to develop coordinated responses to prevent serious violence, this includes VAWG. Work will be required to ensure that policing and partners understand and commit to this in the coming period.

- National work is currently underway in response to the independent review of child social care, national murder reviews, and the independent inquiry into child sexual abuse. Policing, as one of the three statutory safeguarding partners, has a key role in supporting the development of proposals and subsequent implementation. Reforms are likely to further enhance and clarify policing and partnership responsibilities around child safeguarding and lead to broader reforms within the children social care offer.

Key VAWG threat areas

While all forms of VAWG can involve high levels of harm, and individual offenders can abuse and exploit many women and girls in a multitude of different ways, this assessment sought also to look at individual VAWG themes in terms of threat, harm and risk.

As a result, the following were identified as key VAWG threats:

- Domestic abuse

- Rape and serious sexual offences

- Child sexual abuse and exploitation

- Tech enabled VAWG

This judgement is made on the combination of impact on victims, volume and frequency of offences and an assessment of policing’s current capability and capacity to respond to these threats. While stalking and harassment accounts for a large proportion of VAWG (43%), this crime type cuts across domestic abuse and tech enabled VAWG. The proposed focus on activities in the four ‘P’ areas will look to have impact across the entirety of VAWG.

Domestic abuse (DA):

- DA accounts for 17% of all crime recorded in the year ending March 2022.

- DA is not a criminal offence in itself but provides the context in which a high proportion of crimes occur. From domestic homicide (115 adult family and intimate partner homicides with female victims recorded in the financial year 2021/22) to behaviourally abusive coercive control which accounts for approximately 5% of all DA and is rapidly increasing; to sexual offences (33% of rape is DA related).

- DA is also a key driver for stalking and harassment, 32% of stalking and harassment offences are DA related.

- Where the sex of the victim is recorded, approximately 75% of DA victims are female and high rates of repeat victimisation indicate there are several points at which a victim may come into contact with policing.

- Similarly, a significant proportion of DA offenders repeatedly offend. The repeated points at which both victims and perpetrators come into contact with policing provides opportunities to develop enforcement strategies and for effective perpetrator programmes to be commissioned.

- The impact of DA on victims is considerable, ranging from physical, to long term mental health difficulties. Victims are also economically impacted and often require support with housing and other services.

- The Office of the Children’s Commissioner estimates that 25.8% of children under 18 live in a household where an adult has experienced DA. Children are considered victims in their own right and there is considerable evidence that the harms they experience persist into adulthood.

- It is highly likely that the harm caused by DA perpetrators extends beyond the immediate victim, impacting on the wider family and society. This emphasises the importance of children’s needs being effectively addressed by policing and support agencies.

Rape and serious sexual offences (RASSO):

Rape and serious sexual offences (RASSO):

- Rape and serious sexual offences account for 10% of all VAWG; 36% of sexual offences are rape. There is significant underreporting. Rape Crisis estimates that five million women in England and Wales have been raped or sexually assaulted since the age of 16.

- Just under a quarter (24.1%) of sexual offences are committed against children aged 10-14, whilst 25% are committed against children aged 15-19.

- Operation Soteria Bluestone found that stranger rape (where the offender is unknown to the victim) accounts for 5% of rapes; additional police recorded crime data found that stranger offences mostly consist of lone offenders and over half of perpetrators (68.6%) engage victims in conversation before the attack.

- It is highly likely rape and other serious sexual offending is a common feature of domestic abuse, CSEW data indicates that one in two rapes are committed by a current or ex-partner. Operation Soteria Bluestone found that 33% of reported rapes were committed by an intimate partner.

- It is highly likely that the harms impacting victims of sexual offences go beyond the physical and are often long lasting – the majority will have no lasting physical injuries but will subsequently experience mental health illnesses such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and some experience suicidal tendencies.

Child sexual abuse (CSAE):

- The majority of recorded CSAE crimes relate to child sexual abuse (CSA); just under a third of CSAE relates to rape of a child.

- The CSAE threat varies considerably. 90% of CSA offenders are male however, this proportion decreases in cases of indecent images of children (IIOC).

- Child on child offending is the most common form of reported CSA and is particularly high for IIOC offences. The circulation of self-generated indecent images is a significant contributing factor to this.

- CSA in the family environment accounts for just under half of all reported CSA offences.

- There are increasing referrals from partners in relation to online CSA.

- There is an overlap between child sexual exploitation and young females being criminally exploited. Girls are likely to be recruited in the vicinity of their schools.

- Group based child sexual exploitation continues to be of significant political and public interest and subject to review by the Independent Inquiry into CSA and HMICFRS. The recent announcement of the creation of a CSE taskforce within policing in collaboration with the Tackling Organised Exploitation programme and the Vulnerability and Knowledge Practice Programme will seek to improve our understanding of this threat and provide enhanced investigative support to improve outcomes for victims. Proportionally, group based CSAE has consistently accounted for a small proportion of total CSAE data, in Q3 of the financial year ending March 2023, this stood at 4.5%.

Technology and online enabled VAWG:

- The exponential increase and advancement of technology has provided increased opportunities for perpetrators of VAWG to commit offences.

- It is challenging to assess the scale of reported technology enabled VAWG due to data recording practices. Forces estimate that on average 10% of VAWG offences occur online, this is likely to an underestimate. Most VAWG offences will likely have a digital component, even where they do not take place online.

- Most online facilitated VAWG which is reported to police is classified as stalking and is committed by known offenders via mainstream social media. However, there are considerable intelligence gaps in relation to the use of the online space by VAWG offenders and a survey found that most of the online abuse was committed by strangers.

- A fifth (19%) of girls aged 11-16 have received unwanted sexual images, this increased to 33% for 17–21-year-olds. Half (51%) of young people report doing nothing when receiving unwanted sexual content.

- The impact of the manosphere (a network of online communities who promote misogynistic beliefs) on the beliefs and attitudes of young men and boys is raised as a growing VAWG threat.

- Current and future developments of the Internet of Things (IOTs) including smart devices, AirTags and spyware facilitates the monitoring and control of victims.

- The metaverse and development of haptic suits (accessories which deliver sensory feedback to the body) provide additional opportunities for offenders to commit VAWG in a space which is currently unregulated.

- The widespread adoption of privacy enhancing technologies such as end-to-end encryption can pose additional challenges for investigation of online and tech-enabled offending.

- There is clear responsibility for technology and social media companies to ensure that the online space is a safe space for women and girls. The incoming Online Safety Bill seeks to address some of these challenges.

- Industry decisions which undermine the agreed Safety by Design principles reduce companies’ ability to protect women and children on their platforms and will result in less identification and reporting of offending. For example, the implementation of end-to-end encryption by default, without equivalent moderation and safeguarding mitigations on platforms used by significant numbers of children, like Facebook Messenger and Instagram, significantly reduces industry and law enforcement’s ability to protect children.

Key findings for other VAWG threat areas:

Stalking and harassment:

Stalking and harassment:

- Stalking and harassment accounts for nearly half of police recorded crime which falls within the definition of VAWG, DA is a key driver of stalking and harassment.

- One in five women experience stalking in their lifetime.

- Stalking and harassment accounts for 23% of all online flagged offences.

- Due to changes in Home Office Counting Rules it is not possible to accurately assess trends in stalking and harassment.

Adult sexual exploitation and sex work:

- For the purposes of determining an appropriate policing response, sex work is separated into three distinct groupings: “survival sex” for people who have no choice but to participate, “sex workers” for those who see it as better than any alternative and “sexual entrepreneurs” who choose it as a means of living. Harm and risk vary according to the context a sex worker operates in.

- There are large intelligence gaps around the exploitation of women for prostitution. Barriers to accurate identification include forces having limited resources to allow them to prioritise this issue, particularly as victims are often adults, with forces often prioritising resources towards the exploitation of children. Victims may not engage with an investigation because of distrust in the police, insecure immigration status, fear of repercussions by those exploiting them and because often this is a primary source of income for them.

Modern slavery and human trafficking (MSHT):

- Sexual exploitation is the biggest threat area under MSHT which impacts women and girls, 91% of sexual exploitation impacts women and girls.

- Domestic servitude is the second highest form of exploitation in which women and girls are most at risk and often takes place in conjunction with domestic abuse and sexual exploitation.

- Often, women and girls are subject to multiple types of exploitation, where this occurs, criminal exploitation is the most common form of secondary exploitation.

Honour based abuse (HBA):

- HBA covers a multitude of crime types including coercive control (the most common form) and assault.

- Offenders are usually family members and victims are subject to multiple forms of abuse over time.

- There is significant underreporting, recorded crime is estimated to be 1% of the total number of incidents reported to healthcare professionals. Underreporting occurs for a myriad of reasons including shame, worries about childcare, and the perpetrator controlling finances.

Spiking:

- Most spiking reports relate to drink spiking and identified offending is low. A very small proportion of spiking reports result in a forensic outcome which supports a spiking incident.

- Young women are most impacted, the majority of offenders are unknown (87.5%).

Incels:

- Incels (short for involuntary celibate) are members of a group who are unable to find sexual partners and who express hate towards the people they blame for this. They are an emerging, predominantly anti-female, online movement and so the scale of this threat is unknown.

- Males endorsing incel ideology are often young (aged 16-25) and have mental ill health or learning difficulties.

- There is concern about the endorsement of VAWG by incels, in particular the impact this has on boys and men. Development of existing work by counterterrorism policing is being built upon to continue collective understanding across law enforcement of the overlap between VAWG and terrorism.

Next steps

VAWG will remain a key threat, therefore, it is important that policing focuses activity in areas which will have the greatest impact.

VAWG will remain a key threat, therefore, it is important that policing focuses activity in areas which will have the greatest impact.

This assessment identifies the high threats of domestic abuse, rape and serious sexual offences, child sexual abuse and exploitation and tech enabled VAWG.

Policing’s priorities to improve its response to VAWG will be through improved quality of VAWG investigations: enhanced professionalisation of public protection capability and a focus on staff and officer wellbeing by:

- Relentless pursuit of perpetrators: improved identification of repeat, high harm and predatory VAWG offenders.

- Improving the digital forensic response to tackle gaps in capability and capacity to process digital evidence and respond to tech facilitated VAWG.

- Further partnership working on VAWG with a focus on prevention.

- A keen focus on fulfilling data and intelligence gaps to inform the threat picture of VAWG.

This is the first STRA and is the foundation upon which further insight will be built. The intelligence gaps identified during this process of assessment will inform future intelligence and information gathering activity to mature the informed VAWG threat picture.

Our priorities will be to build a greater intelligence base for understanding:

- The scale and nature of VAWG reported to other statutory agencies.

- The prevalence of VAWG across black and minoritised communities and how this impacts the policing and partner response

- The involvement of VAWG perpetrators in other forms of offending and what opportunities this presents policing and partners with for disruption.

- The prevalence of VAWG committed online and the forums in which it is committed.